The price for a new job is $1,500, the recruiter says.

It’s the equivalent of at least four months’ wages for an average person in Mexico’s Veracruz state. But the deal is solid, the recruiter promises. It comes with a place to live in Canada, and help finding work that could pay 10 times the wages of a local job.

"If you’re a worker here, you can work there," the recruiter advises. "Use us like a springboard."

Click here to listen

Click here to stop

"¿Y como cuánto pagan?"

"How much do they pay?"

"Mínimo, el salario depende del patrón, pero mínimo son $12 dólares."

"The salary depends on the boss, but the minimum is $12 an hour."

"¿Y ya con los compas allá me recomiendan lugares?"

"Ok and the contacts there will recommend places to work right?"

"Ahí tu mismo vas eligiendo buenas opciones. Ahorita tengo un muchacho que le están pagando $26 dólares la hora. Casi $65,000 pesos al mes ..."

"Yes, You will choose good options for yourself. Right now I have one guy who is making $26 an hour - that’s 65,000 pesos a month ..."

"¿Pero tú me recomiendas más Canadá o Estados Unidos?"

"So do you recommend going to Canada or the United States?"

"Depende de tus obligaciones. Si quieres algo ya, Canadá ..."

"It depends on your goals. If you want something right now, Canada ..."

The man on the phone has provided this information to an undercover journalist working for the Star, posing as a would-be migrant.

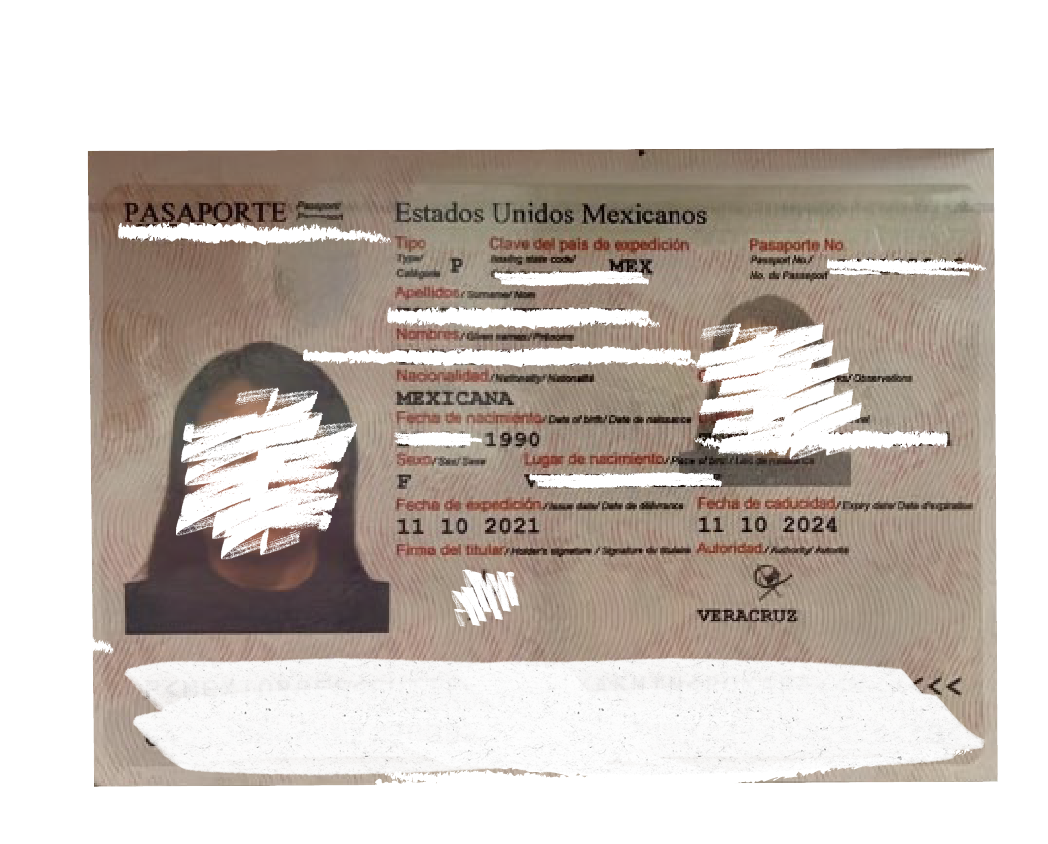

José Ayala Martínez’s journey to Toronto began with one such recruiter.

Martínez was looking for new opportunities when he saw a Facebook post promising work in Canada. He believed he was signing up for the same government program that brings temporary farm workers to Canada, he would later tell police.

What recruiters actually provide, in most cases, is a tourist visa that expires after six months — not the work permit someone like Martínez would need to apply for jobs and start a new life.

There are almost no legal channels for working-class immigrants to come to Canada as permanent residents, said Deena Ladd of the Toronto-based Workers’ Action Centre. This creates a market for recruiters and agencies, who offer people opportunities abroad that their home country cannot provide. In reality, says Toronto Victim Services’ head Carly Kalish, they offer little more than "marketed smuggling."

These recruiters, according to court documents, "sold the dream" to Martínez and others. His real name is now subject to a publication ban; the Star has used an alias to protect his identity. The police and legal records relied on in this story were accepted as fact in the course of a months-long court proceeding.

The recruiting firm Martínez contacted regularly posts online photos of happy clients at their overseas jobs, advertising wages of up to $22 an hour.

"Canada is waiting for you," reads one.

So Martínez paid his $1,500 fee and booked his travel north. He had been given the name of a woman in Toronto, who would pick him up at Scarborough Town Centre and take him to his new home. It was the same woman who Cruz says convinced her to hand over her passport and life savings.

Her name was Luz Adriana Gonzalez Valbuena.

Valbuena originally came to Toronto from Colombia as a refugee. Here, the short, blond mother of four seemed to have built a prosperous new life: she drove a blue Dodge Ram pickup truck and owned a company called Roofers Barry that neighbours thought was in the construction business.

Valbuena also leased at least five properties across the GTA, including the home where Cruz rented near Jane and Sheppard. One was a house on York Mills Road, where neighbours observed young men and women arriving regularly, suitcases in tow.

Another was on Castledene Crescent in Scarborough, where Valbuena first brought Martínez.

One worker later told police the living conditions were "made to feel like (a) kidnapping." Valbuena confiscated passports from new arrivals as part of what she called a "deposit," according to court records. Once inside, tenants learned Valbuena didn’t actually provide rooms. Instead, she rented out "spaces" in the basement at a cost of $500 a month. Residents could purchase an inflatable air mattress from Walmart and sleep on the floor.

Tenants were also banned from using the kitchen, and were instead told to pay $15 a day for Valbuena to provide a small breakfast sandwich and dinner. They were also told not to go out in large groups or make noise. Some were told not to speak to each other at all.

At the two-storey house on Castledene, residents would later tell police, up to 44 people had been living there at once.

Valbuena’s company, Roofers Barry, operated like a temporary help agency, although it was not registered as one with the province.

Court records identify at least a dozen employers where Valbuena sent workers, from a small lawn-care company in Toronto to the Marriott Hotel in Markham. The Marriott said it could not respond to the Star’s questions beyond saying that the company co-operates with police.

Valbuena’s workers sometimes worked six days a week for 10 to 13 hours a day, according to court records. But their pay would go directly to Valbuena. Of a $1,600 cheque, Valbuena would often pass on less than half of those earnings to the worker.

Police recovered cell phone records that showed Valbuena communicated with employers. When contacted by the Star, several claimed they didn’t know Valbuena or recall doing business with her.

One employer, however, said he remembered their first encounter. Kourosh Rouhani, a roofer, was driving his company-branded truck near Woodbine and Steeles avenues when Valbuena waved him down and asked if he needed workers, he told the Star. Valbuena offered a rate of $15 an hour, of which Rouhani believed workers received $11 to $13 — less than minimum wage at the time. The relationship soured, he said, after Valbuena jacked up her rates.

Over the past decade, the number of active agencies has steadily risen across Ontario. But relying on them to source workers can obscure exploitation — or, in some cases, allow employers to turn a blind eye to it, said Ladd of the Workers’ Action Centre.

That is because hiring through middlemen relieves companies of some of their obligations to workers by shifting much of the legal responsibility for workplace rights and injuries to the agency.

Court records identify just one employer who scrutinized Valbuena’s practices before agreeing to do business with her, going so far as to visit workers’ accommodation, the documents say.

After seeing their living conditions, he refused to partner with Valbuena.

Around a month after he started working through Valbuena, Martínez realized that the life promised by his recruiter was a lie. Nonetheless, his wife and two children eventually joined him in Canada, according to court records, after his eldest son was the target of an attempted abduction in Mexico.

Martínez was unable to leave Valbuena’s home without permission, he told his wife. Instead, Valbuena offered to rent the family a bedroom the four of them could share. She also offered work to Martínez’s wife as a caregiver to her youngest children, a boy of about 10 and a girl of around three.

At first, the arrangement seemed promising. But soon, Martínez’s wife grew concerned.

"In a way, I’m scared to be in the streets in case I see her or people who know her. Sometimes I feel powerless because I was left humiliated"

— Victim’s statement to court

Her husband worked all the time. At his first job, where he often worked up to 12-hour days, he had expected a wage of $16 an hour. His first payment from Valbuena, however, did not add up to the hours he had worked. This continued as Valbuena shepherded Martínez to subsequent jobs: a Richmond Hill meat packer, an Etobicoke contractor, a cleaning company that deployed him to retirement homes.

Valbuena kept finding reasons to withhold wages, Martínez later told police. A "problem" at one of his employers meant Valbuena had to give them $2,000 rather than pay Martínez, she informed him. When items — like her Burberry bag — allegedly started going missing from the house, she blamed him and demanded $5,000. When Valbuena’s boyfriend racked up $800 in Hwy. 407 charges, Martínez was ordered to cover the cost.

Martínez could not get his passport back until his "debt" was paid off, Valbuena said. Meanwhile, she began forcibly separating the Martínez family from their son, taking him away from the house for days at a time without the parents’ consent.

"(Martínez’s son) would seem sad about being gone," a summary of a family interview with police reads. "He wouldn’t say what they did."

For many workers, it was difficult to escape Valbuena’s control.

"It made me feel like an object that could be manipulated that at any moment they could just get rid of me."

— Victim’s statement to court

Most of Valbuena’s tenants didn’t speak English and only had their Mexican phones, recalls Cruz. Valbuena didn’t provide Wi-Fi — making communication with the outside world next to impossible.

Tenants feared Valbuena, who repeatedly suggested to them that she had links to cartels or "bad people" in Mexico, court records say; Valbuena kicked out three workers after they showed their employer a video of their living conditions. One ended up temporarily living under a bridge.

Even if they escaped, many had nowhere to go. Toronto’s emergency shelters are at capacity, and without legal status in Canada, workers are ineligible for housing subsidies.

Cruz, who was not a complainant in the case against Valbuena, only escaped after a chance encounter at a laundromat. Overhearing a fellow patron speaking Spanish, she approached her and explained what had transpired at the Jane and Sheppard house. Appalled, the woman took her to Tim Hortons, bought her a coffee, and made a plan to pick her up the next day with whatever belongings Cruz could collect.

Cruz had spent a month being ferried around by Valbuena to various homes and construction sites to clean. She says she was never paid for the work.

By the time Valbuena was exploiting workers, she was already known to police.

A friend, Yadira Barrera, told the Star she knew Valbuena two decades ago, when both women were living in North Carolina. She remembers Valbuena as a dedicated but struggling mother whose partner at the time had "almost killed her."

Valbuena juggled odd jobs like cleaning, and had left Colombia seeking a safe and secure life, her friend said. But even in Canada, where Valbuena was granted refugee status in 2009, this didn’t appear to materialize.

In 2013, she was caught up in a jewelry heist in which a supplier was robbed of $700,000 in gold and diamonds. After the theft, Valbuena told members of the Toronto Hold Up squad that her husband — who she had recently charged with assault — was involved. She alleged that he had left some of the stolen goods in her possession, and Valbuena agreed to retrieve them while police arranged for her to stay at a women’s shelter.

However, she then stopped communicating with the authorities and refused to co-operate further until her family in Colombia was entered into a witness protection program. The following year, amid separating from her husband, she also pleaded guilty to assault with a weapon after plowing into his car with her own.

Barrera lost touch with Valbuena for many years after she moved to Canada, but eventually reached out again upon learning of her old friend’s divorce. Phone records recovered by police contain text exchanges between the two women in 2019, in which Valbuena expresses concern about "threats" made by an ex-boyfriend, and about being caught up in something "illegal."

Valbuena did not respond to questions from the Star sent to her lawyer. But letters from her parents and children presented in court provide insight into at least one formative event in her life, which her lawyer said served as the basis of her successful refugee claim in Canada. At 16, she was kidnapped by FARC guerrillas and forced to spend "six months in a hole in the jungle." There, she was sexually assaulted.

On an early summer’s morning last year, residents of York Mills Road awoke to a commotion as police and border agents descended on the three-bedroom house leased by Valbuena.

Investigators were acting on a tip from the Mennonite New Life Centre Toronto, which had been approached by two workers claiming Valbuena was trafficking people and housing them at two properties. One was the York Mills home, where Valbuena occupied the main floor with her little boy and girl, and kept workers in the basement. The other was a small Scarborough bungalow on Vauxhall Drive, where the Martínez family was now living.

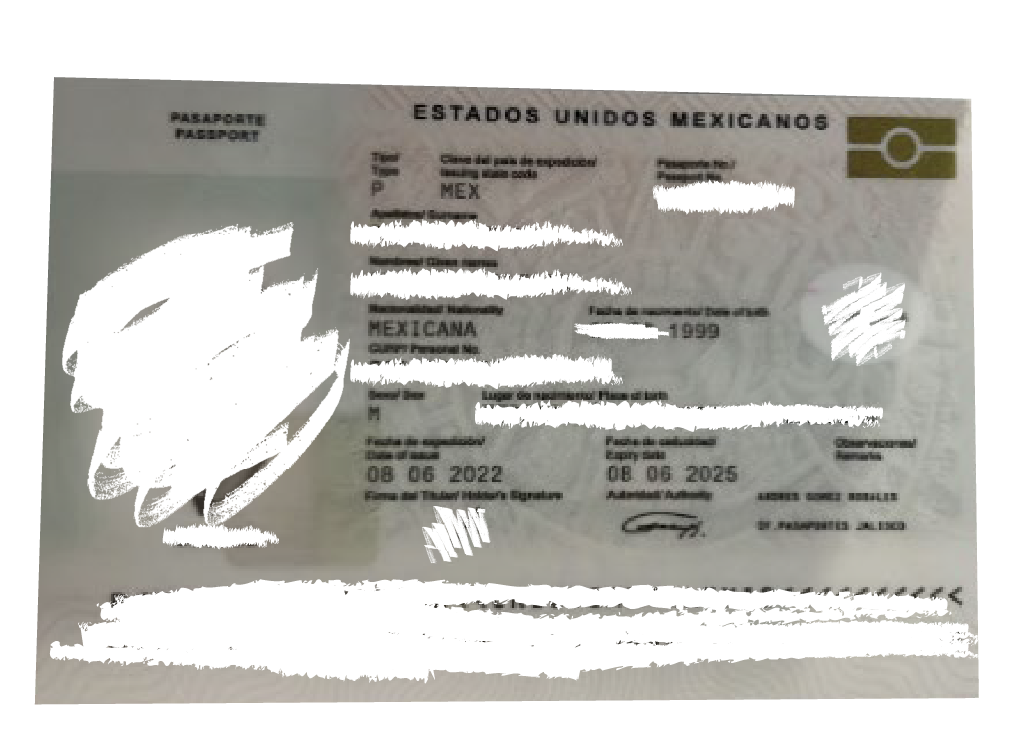

Amongst the items recovered by police was Valbuena’s purse. It contained the passports of more than two dozen Mexican nationals.

As authorities combed through the York Mills Road house, the inhabitants were moved to a TTC bus stationed on the street, its windows blacked out. From there, the workers were taken to a hotel where they were provided support by the FCJ Refugee Centre. In total, 61 victims were identified, said Tsering Lhamo, the organization’s associate director, who attended the scene after the police takedown. With charges laid, the workers were eligible for Temporary Residency Permits, a special visa for trafficking survivors.

Click here to listen

Click here to stop

"Yo desde que llegué para mí fue algo muy raro."

"From the moment I arrived it was very strange."

"La verdad es que sentí una humillación hacia mi persona."

"Truth is I felt great humiliation towards me."

"Eran como cinco o seis de la mañana ... escuché pasos y entraron a la recámara."

"It was around five or six in the morning ... I heard footsteps and they entered the room."

"Yo rezaba 'por favor que venga la policía por favor que venga la policía.' Cuando por fin llegó, yo lloré fue de emoción porque realmente yo no sabía como salirme de esa casa."

"I used to I pray 'please let the police come, please let the police come.' When he finally arrived, I cried out of emotion because I really didn't know how to get out of that house."

Within three days, FCJ had helped 44 survivors apply for the renewable six-month permits, and eventually received approval from Immigration Canada for all of them, said Lhamo. More than 20 of these workers provided statements to police detailing Valbuena’s "exploitative" practices.

In March, Valbuena pleaded guilty to 10 counts of human trafficking and nine other related charges, including withholding workers’ travel documents. She was sentenced to eight years in prison, becoming only the second person in Canada to be convicted on similar grounds.

The Crown called Valbuena’s scheme an example of "industrial" labour trafficking that had devastating consequences for survivors. The after-effects were described in victim impact statements translated and read aloud in court. One belonged to the Martínez family.

In it, Martínez describes his withheld pay, workplace injuries for which he was denied medical attention, and the constant threats issued by Valbuena. In total, he spent four years living and working with Valbuena, during which time he became increasingly depressed.

On two occasions, his statement says, he tried to take his own life.

After Valbuena’s arrest, a friend sent Cruz a picture of the mug shot. Looking at the photo, Cruz says she began to cry.

"Many people sold their house, their car, to be able to come to Canada, just so this woman could take away everything they had," she said. "I think she deserves to be where she is."

In court, the judge praised the police and the Crown for their exhaustive investigation that treated victims with "respect and dignity, as they deserve."

But Deena Ladd of the Workers’ Action Centre has deep concerns over where trafficking proceedings ultimately leave survivors. Criminal prosecutions do not provide an avenue for workers to recover unpaid wages. Nor do they address the root causes of exploitation.

"You’ve got that kind of nexus between these terrible immigration laws and horrific labour laws," she said.

As the investigation into Valbuena concluded, survivors applied to the federal government to renew their six-month visas, Lhamo told the Star. The permits were crucial — if limited — lifelines, connecting workers and families to health coverage and allowing them to work. But only two individuals received temporary extensions, which have also now lapsed.

Valbuena’s survivors — including those who contributed evidence to help prosecutors put her behind bars — can no longer access supports like therapy for post-traumatic stress, said Lhamo. They are all at risk of deportation.

"Now all the victims are on their own," said Lhamo. "They are abandoned."

Some have returned to Mexico, the place they used their life savings to leave. Two months after Valbuena pleaded guilty to human trafficking, the Star called two of the recruiters she had used there.

The cost to head north is still $1,500, according to the woman on the other end of the phone. She will be here to help with the journey, as long as you are careful not to refer to her business as anything but a travel agency.

Once you arrive at Toronto’s airport, the woman says, a ride will be waiting, ready to take you to a new life.

Click here to listen

Click here to stop

Nosotros les damos un plan de placer, les damos una reservación de hotel, de la cual no se paga ni se ocupa, pero tenemos que llevarla para poder pasar la inmigración. Estando allá tienes que pagar una renta. La renta es aproximadamente entre $1000 a $1300 al mes y eso incluye que vayan por ti al aeropuerto. Incluye que te den un lugar en la casa. Que te den trabajo. Una vez que llegue al aeropuerto, los recogen y regularmente están trabajando entre cinco y siete días."

"We give people a travel plan, a hotel reservation that you won’t pay for but you need it to cross the border…Once you’re there you have to pay rent obviously, that will be around $1000 to $1300 for the first month. That includes pick up from the airport, a place to live, a job. Once you get to the airport you’ll be working within five to seven days."

"¿Qué ciudad dijiste?"

"In Canada, what city did you say?"

"En Canadá si quieres ir de turista a Toronto y me parece que a Lemington todavía tenemos."

"In Canada, you have to go as a tourist, you can do that either in Toronto or I think Leamington is still available."